Did Cinema Portray Epstein’s Island Before Its Revelation?

With Jeffrey Epstein’s name resurfacing in the headlines following recent court developments and the release of previously unpublished documents, several older films have experienced an unprecedented wave of attention, most notably Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut and Eli Roth’s horror film Hostel. This renewed interest did not arise randomly; it reflects a growing public sense that cinema can sometimes capture facets of reality that only emerge much later.

From Symbolism to Suspicion

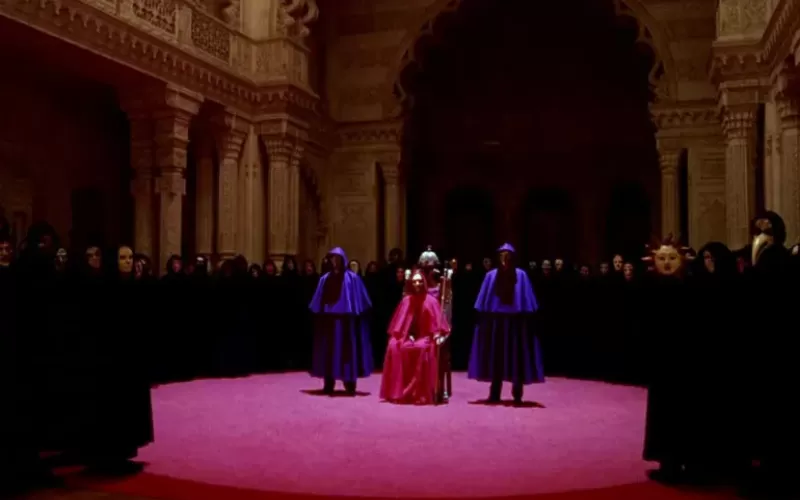

Kubrick’s 1999 film Eyes Wide Shut was never intended as a depiction of a specific conspiracy or real-world criminal networks. Yet it presented a closed world in which an elite, insulated by wealth and influence, operates according to its own rules, beyond accountability. As discussions about the Epstein case intensified, this cinematic world began to be invoked as a visual approximation of the hidden lifestyles later revealed among the implicated elite.

Comparisons circulating on social media went beyond general ideas, highlighting visual and behavioral details: isolated mansions, closed gatherings, silent rituals, and anonymous participants. The conversation thus shifted from a purely artistic question about Kubrick’s intentions to a broader cultural question about cinema’s ability to capture the structure of secret power before it is publicly exposed.

A Film of Anxiety, Not Revelation

It is crucial to distinguish symbolic representation from documentation. Eyes Wide Shut is adapted from Arthur Schnitzler’s novella Dream Story, a psychological work focused on jealousy, bourgeois identity, and moral fragility. Kubrick transposed these themes to a contemporary American context, using ambiguity as a central device. He never explained the nature of the masked society nor offered viewers conclusive answers.

This ambiguity gave the film its enduring relevance and made it applicable to any major scandal involving elites. The film does not assert that such rituals actually exist; rather, it suggests that the possibility of a parallel world governed by different rules is frightening in itself.

Hostel: From Hyperbole to Moral Shock

On the other end of the spectrum, Eli Roth’s 2005 film Hostel relies less on symbolism and more on direct shock. It portrays a wealthy elite paying to torture and kill victims in locked rooms under the auspices of a transnational secret organization. For years, this premise was dismissed as cinematic exaggeration, belonging to the farthest reaches of horror fiction.

However, the revelations about Epstein’s network—systematic exploitation, the transport of victims, and complicity of powerful figures—prompted some viewers to reconsider the film’s underlying premise. Not in terms of explicit violence, but in the core idea: transforming humans into commodities within a perverse system of privilege, protected by wealth and power.

Why Do These Films Resurface Now?

The renewed interest in these works does not imply they predicted actual events. Rather, it reflects a deep crisis of trust in official narratives. When audiences perceive the truth as partial or delayed, they turn to popular culture for meaning. In this sense, films like Eyes Wide Shut and Hostel serve as mirrors of collective anxiety rather than evidence of wrongdoing.

This pattern has recurred historically with other films: All the President’s Men resurfaces during crises of faith in journalism, Chinatown during debates over financial and legal collusion, and The Truman Show in an era of pervasive surveillance. Cinema does not reveal reality itself; it provides the language through which audiences interpret it.

There is no direct evidence linking the works of Kubrick or Roth to Jeffrey Epstein’s crimes. Yet the parallels perceived by the public are not purely illusory; they emerge from the intersection of cinematic imagination, which explored the architecture of power, and real-life revelations exposing the fragility of justice in the face of elite influence.